"Characteristic of her great wit, self-critique and introspection, this is an honest rumination of the role of women in music."

The following is Phyllis Tate in her own words discussing her contemplations and frustrations of being a woman in a male-dominated profession. Characteristic of her great wit, self-critique and introspection, this is an honest rumination of the role of women in music.

Does this sound a bit formidable? Not so long ago, at a party, my hostess introduced me in these terms, and the reaction was immediate - absolute horror registered on the faces of the other guests, and they retreated as quickly as they decently could to the farthest end of the room. If one had been labelled woman painter, or woman writer, would the impact have been so marked? Perhaps, I reflected, it’s because there are so few women composers. I made a kind of survey and found, to my surprise, nearly 80 of them ranging from Post Domesday up to the present day. The earliest was a Benedictine Abbess called St. Hildegard, born in 1098, who wrote monophonic choral music. The first English woman I came across was Eliza Turner, who died in 1756, the year Mozart was born. Also from this period was a rather pathetic figure in the shape of Lucille Gretry, daughter of the Gretry. She wrote an opera at the age of 13 which was successfully produced, - her father helped to score it - and another one a year later. She died at the age of 20 - perhaps the strain of these operatic ventures proved too much for her. The next revelation was that the 19th century produced not only a fairly big crop of female composers, but also that they were most prolific, and their compositions covered a wide range. One always tends to think of Victorian ladies as being rather inhibited and repressed, but not this batch. What about Alice Mary Smith who managed to get through 3 Cantatas, 2 Symphonies, 4 Overtures, a Clarinet Concerto, 3 string Quartets, 4 Piano Quartets, and so on. And how about Julia Weissberg. She studied under Rimsky-Korsakov at St. Petersburg Conservatoire (and later married his son, by the way). But not before she was expelled from the Conservatoire for taking part in a demonstration against the Director - a foretaste of Women’s Lib, obviously.

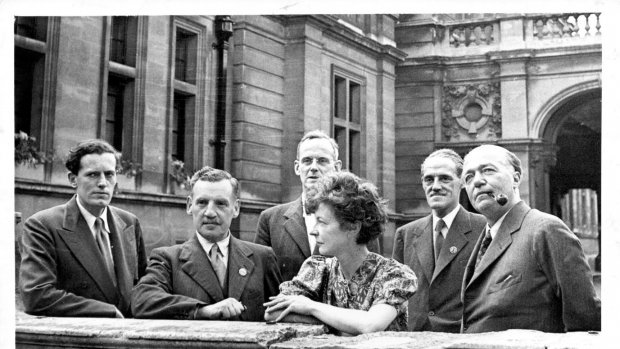

The English Doyenne of this era was undoubtedly Dame Ethel Smyth. Unquestionably, she was the pioneer of the modern British woman composer, and in her early days that wasn’t an easy profession. She was a fighter for women’s rights. She had to be, she came from a distinguished Army family where it was considered immoral for any well-bred young woman to do anything but assist at tea parties and arrange the flowers. When I was very young, I was taken to have lunch with her at her country home during the last phase of her life. My escort was an erratic driver, and he insisted on stopping off at every pub on the way, we arrived extremely late. We were greeted by an irate Dame Ethel, who, in a stentorian voice, and with blue eyes ablaze, barked out “How like a man” and then, in a more subdued voice to me “Quick, you’d better go to the lavatory, there’s a tin of toffees for you in there”. I suppose she must have thought me too infantile to be even housetrained! After lunch, I bashfully produced my latest effort, a cello concerto. She was very kind and encouraging (perhaps because she couldn't hear it), and when it was eventually performed at a concert in Bournemouth, she insisted on making the long journey, and sat in the front row banging her umbrella up and down in time (or what she thought was in time) with the music, much to the embarrassment of the performers and the audience.

It appears, then, from this galaxy of feminine talent, women have by no means been idle in the field of composition, but what about the quality of their output. Maybe some musicologist should delve into all these opuses in case a neglected masterpiece is reposing on some dusty shelf. But I can't help feeling that if any of these industrious ladies had been real masters (or should I say mistresses), the fruits of their labours would have come to light. Anyway, as far as one knows, there has been no woman Beethoven or, for that matter, no woman Rembrandt, or a female Milton. Perhaps the exception where women can be compared with the best of men's achievement is in prose literature from Brontes and Jane Austen, right up to today.

Can it be that writing is a more basic and natural mode of expression. After all from the infancy onwards, one gets accustomed to the sound and meaning of words without having to undergo any specialist training as in the other arts. What is it, then, that has prevented women rising to really great heights in Composition. Is the reason partly a biological one, that in the woman creator there is something of a dichotomy, and that the process of giving birth to the human species is in conflict with the imaginative side of creativity – that this division of energy saps just that extra strength and inspiration needed to trigger off and sustain the full scale masterpiece. Another and more down to earth reason could well be the burden of domestic responsibilities. In the great majority of cases, these still rest on the woman's shoulders. I suppose the ideal would be more sex equality, with man contributing a bigger role in the more mundane activities of life. Will this ever happen? Perhaps not in my time, but I would like to feel that in the not too distant future a female Wagner might arise (with, no doubt, a Mr. Wagner in the background meekly doing the household chores).

Composition is probably the most elusive and, certainly, the most laborious of the arts. Think of all those notes and barlines in an opera full score or a symphony. How nice it must be for a writer, armed only with a wad of plain paper and a typewriter. I guess I'll opt for that profession when it comes to my reincarnation.

One last plea. Either one is a Composer or one is not. I can't imagine a day devoted to men, so why do we still need one about women? This does seem to me an admission of a lingering inferiority complex, that we have to assert ourselves so vigorously.

[Read the rest of the series here.]