50 Things is a series of short blogs marking the 50th anniversary of the British Music Collection, using items from the collection to offer a bold new perspective on the recent history of new music in the UK. #BMC50

Article by Robert Barry

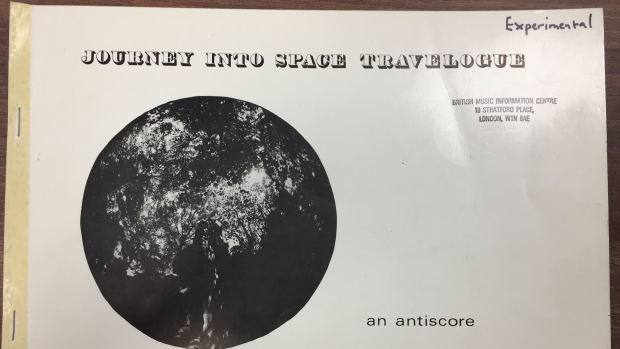

The item is a sheaf of slightly yellowing pages fastened by two staples on the left hand edge. “Journey Into Space Travelogue”, the title announces itself in a somewhat old-timey, ‘playbill’ type font. And then lower down the page, more mysteriously, “an antiscore”, suitably lower-case and modernist of typeface. The old Stratford Place W1 address of the British Music Information Centre is stamped in the top right corner with the classification “experimental” added in black parker pen.

But what is an “antiscore”? And how can one “journey into space” through sound?

The composer is Trevor Wishart and his foundational role in the development of sound art, site-specific composition, and digital music have long assured him a place as one of Britain’s most important 20th century composers. Born in Leeds in 1946, the son of a factory worker, he studied music at Oxford, later gaining an MA from Nottingham University. But in 1969, after the death of his father, he abruptly abandoned conventional composition, bought himself a small portable tape recorder and began collecting sounds – primarily industrial sounds, recorded at factories, workshops, foundries, and power stations. Mixing these recordings with sounds taped from the television news (specifically, the Apollo landings), or live music improvised with friends and students (like a young Jonty Harrison and Steve Beresford), Journey Into Space was the first of these experiments to be fully-realised, recorded and released - across four sides of vinyl, issued by private press in 1975.

“The invention of direct sound-recording techniques should be seen as the most important fact in music history since the birth of analytic music notation in the Middle Ages,” Wishart writes on the opening pages of the item at hand. It is an “antiscore”, then, because it is not a map or plan for how an ensemble of musicians might construct or go about performing Journey into Space; rather it is intended to serve as “an account” of how he had already gone and done it. Between its pages, you can find fragments of traditional notation, verbal descriptions of actions, graphic diagrams, and many other kinds of symbolic representation, all of which is intended to serve, Wishart writes, as “an antidote to a thousand years of notated-music history.” In appearance as well as sound (the recording is now available on Bandcamp), Journey into Space is quite unlike anything else of its time or after – even amongst Wishart’s own eclectic oeuvre. A true singularity, way out on its own.

--

Robert Barry is a freelance writer and editor, based in London, UK. His byline has appeared in publications including The Wire, Frieze, Art Review, Fact, The Atlantic, Wired, Thump, Motherboard, Sounds Like Now, BBC Music, The Guardian, Mute, Mousse, New Humanist, Seismograf, Plan B, Exeunt, The Line of Best Fit, White Noise, Vertigo, Electric Sheep, Film-Philosophy, Eat Me, and Apollo.

He is currently technology and digital culture editor at the online literary journal Review 31, visual arts editor at The Quietus, and a member of the faculty at London’s Institute of Contemporary Music Performance. His book, The Music of the Future, a history of speculative music, was published in March 2017 by Repeater Books.