For our 50 Things series, author and musicologist Robert Adlington re-traces the distinctive career of composer George Newson. #BMC50

Article by Robert Adlington

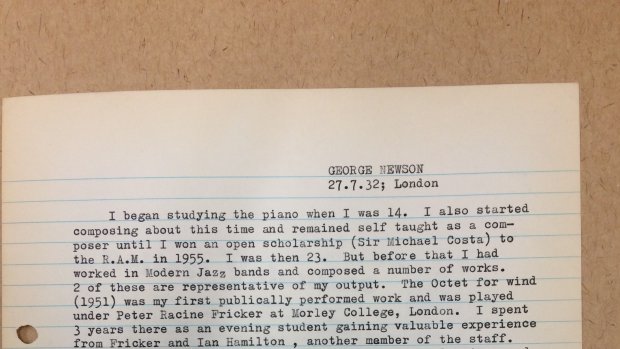

A single sheet of typescript: hardly the most impressive or eye-catching of the 60,000 ‘things’ that make up the British Music Collection’s physical archive, now housed at the University of Huddersfield. Yet for me, this single sheet encapsulates why the BMC matters. It is to be found in one of the collection’s 1200 ‘composer files’, dossiers of materials lovingly assembled by the former custodians of the collection at the British Music Information Centre in London. These files, each devoted to a single composer, contain a deliciously unpredictable assortment of items, ranging from press clippings to publishers’ information, concert programmes to journal articles, and from time to time unique material provided by the composers themselves. My ‘thing’ belongs to this last category: to my knowledge, the text has never been reproduced in full anywhere else.

Who is George Newson? I found myself asking that question as I read the fascinating account of Newson’s spectacular oratorio Arena (1971) in Michael Hall’s book Music Theatre in Britain 1960-1975. A Google search yielded precious little additional information. Where else to go, then, but the BMC, which holds not only a good number of Newson’s compositions but also a composer file that, as it happened, contained this unique document. Eventually, I was also able to track down the composer himself, who lives near Rye in Sussex, and to spend a wonderful day in his and his wife’s company. But, at 84 – albeit in rude good health – his memory was inevitably hazy on some details of his early career. This typescript document, evidently prepared by the composer in the late sixties, offered valuable clarification.

The short autobiography presented in this document tells us much, not just about Newson, but about the history of British music after 1945. Newson, born into modest circumstances in south-east London, first learnt to play and read music as a child evacuee in Somerset. Scholarships to Blackheath Conservatoire and Morley College allowed him to develop as a performer, while he earnt money as a dance-band musician. The studentship at the Royal Academy then brought him into contact with key figures in British new music, including close contemporaries Harrison Birtwistle and Hugh Wood, and encounters with leading European composers at Darmstadt and Dartington quickly followed. The relationship with Berio was especially significant: Newson recalls hosting Berio in the Sussex countryside, walking together to a nearby farm to satisfy the Italian’s request for fresh milk.

Newson’s Arena, commissioned by William Glock for the Proms, attests clearly to Berio’s influence, especially the Sinfonia. It deploys diverse singing styles, complex multi-layered textures, and allusions to popular traditions to dramatise texts that vividly document the political and social tensions of the era – all of this embedded in a ‘variety-show’ format that saw the compère Joe Melia quipping with conductor Pierre Boulez. Following this high-profile premiere, however, the demands of family life, a succession of teaching jobs, and a distaste for the metropolitan new music circuit contributed to a dip in public visibility for Newson’s music. The rich holdings of the BMC – and perhaps especially its composer files – help to ensure that such circumstances do not dictate who is remembered and who forgotten, as we tell and re-tell the story of British contemporary music.

Robert Adlington holds the Queen’s Anniversary Prize Chair of Contemporary Music at the University of Huddersfield, where he is a member of the Centre for Research in New Music (CeReNeM). He is the author of books on Harrison Birtwistle, Louis Andriessen, and avant-garde music in Amsterdam during the 1960s. His article on George Newson’s Arena will appear in the Journal of the Royal Musical Association later this year. Twitter: @Huddlington.