"...Phyllis was later to become dissatisfied with most of this early work, committing nearly all of the scores to flames." #BMC50

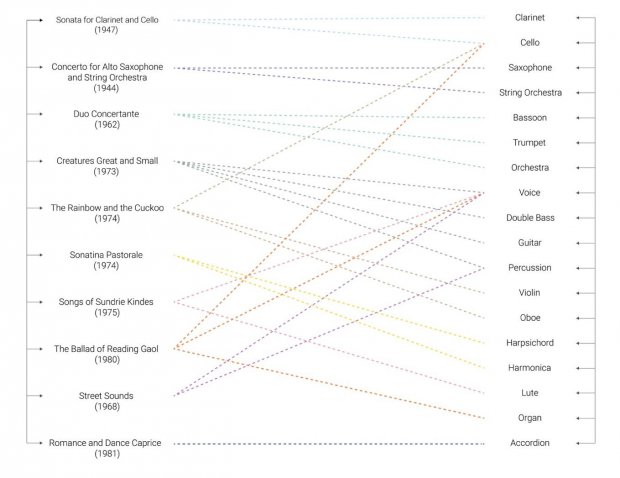

Despite favourable reviews of her compositions during the 1930s, Phyllis was later to become dissatisfied with most of this early work, committing nearly all of the scores to flames. A succession of new pieces however, relaunched her career: Concerto for Alto Saxophone and Strings (1944), Nocturne for Four Voices (1946), and Sonata for Clarinet and Cello (1947). These works established Phyllis as a successful composer, known for an unorthodox approach. They reflect her life-long fascination with unusual combinations of instruments, and her interest in drawing out to maximum effect the poetic potential of the human voice.

Phyllis was a quiet maverick, unwilling to be recruited as a member of any particular contemporary movement, musical or otherwise. In 1986 writer and editor Robert Matthew-Walker eloquently summarised Phyllis’s motivations:

Phyllis Tate has always regarded herself … as an instinctive artist - that she could no more help herself being a composer, or the way in which she writes, any more than she had any say over the colour of her eyes. (‘Phyllis Tate at 75’ in Music and Musicians, April 1986)

The years 1944 to 1947 marked a high-point in Phyllis’s early career, but these were followed by four years of illness. Her life was punctuated by periods of both physical and mental ill-health. Extremely self-motivated and with a burning creativity, she also had great self-doubts. She suffered from depression and anxieties, always exacerbated by being too unwell to compose to her own high standards. Reconnecting with her muse proved undoubtedly to be her healer, and in 1952 she wrote her String Quartet to a positive reception, finishing it just in time for the birth of my mother. This marked the end of a difficult period and the beginning of a musically creative thirty years. Her output became varied and extensive, ranging from a popular light orchestral suite London Fields (1958), and the more experimental The Lady of Shalott (1956) for voice, piano, celesta and percussion, through to music for schools, and a full-scale opera The Lodger (1960). Phyl’s reputation grew and she enjoyed collaborations with many prominent artists of the time.

In her sixties, Phyl’s health started to decline. Despite this, several of her most critically acclaimed and original pieces came from this period. These included: St. Martha and the Dragon (a choral work); Explorations Around a Troubadour Song (for solo piano); Apparitions (for tenor, harmonica, celesta, viola and percussion); and in 1975, The Rainbow and The Cuckoo (for oboe and strings). Increasingly eclectic, she continued her musical journey, taking lessons in African drumming and learning the piano accordion. In her final years however, Phyl struggled to write, and with that came great despair. At the age of 76, she passed away, leaving a potent legacy and a large body of work.

Some thirty years after her death, Phyllis continues to inspire a young generation of musicians to forge their own path and develop their own individual voice.

All I can vouch for is this - writing music can be hell; torture in extreme; but there’s one thing even worse; and that is not writing it. (Phyllis Tate, 1979)

[Read the rest of the series here.]