In partnership with the LGBTQ+ Music Study Group, we invited writers, researchers and thinkers to pitch us editorial on queer music, sounds and the people who make it. The first of these - by j.n.m. redelinghuys - is published today.

In partnership with the LGBTQ+ Music Study Group, we invited UK-based writers, researchers and thinkers to pitch us editorial on queer music, sounds and the people who make it. Today we're publishing the first of these - by j.n.m. redelinghuys -"Hearing In-Between: The Musical Possibilities of Queer Spaces".

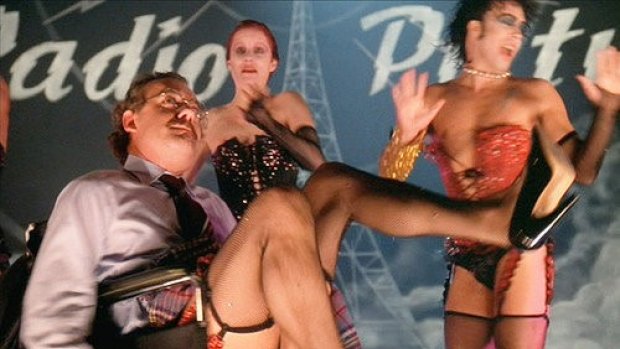

I clearly remember my first experience of attending a midnight screening of Rocky Horror Picture Show. I knew all the words (I must have watched it hundreds of times as a questioning teenager) but I wasn’t quite sure of the actions, the responses, the rituals, including many lewd references to people’s anatomies that I won’t repeat here. I was lucky enough to sit next to an immaculately dressed Frank-N-Furter who showed me what to do, what to say. There were at least two other notable Franks in the theatre. Off course there is Tim Curry’s fabulous performance on screen. Midnight screenings also have a ‘shadow cast’, members of the audience who act out the film in front of the screen, guaranteeing yet another Frank. All three were dressed in drag, but they also performed drags of each other, each remaking the transvestite from Transexual, Transylvania in their own unique way.

But who should I look at? Who was the ‘authentic’ Frank? To what extent was authenticity positive? I was at risk of looking at one of them straight (read: heterosexual) on. To do so would confirm one of them as having a ‘real’ gender, while those I could not see would would fade into the background, back into the closet. There was an alternative: I could look to the spaces in between, where I couldn’t see any of them. Rather than concentrate on what their identities were, I could look to where the theatre was empty, where there was no ‘identity’, no bodies, where nothing was certain. We so often crave for representation, to confirm ideal queer bodies on stage, that we lose sight and sound of how, in Judith Butler’s terminology, these genders can be troubled. Perhaps it’s in these spaces of uncertain absence that we can imagine new possibilities that always question, always disrupt, always queer music itself.

This is a relationship between self and other. I’m not conflating nor am I saying there’s an abyssal divide between the two. They’re different, and there’s an exchange at play, from one to the other and back again, that disrupts the certainty of both. This exchange is everywhere in music making, as we interpret and perceive different media in different contexts, times, spaces, and identities. The French-Algerian feminist author Hélène Cixous writes extensively on this exchange. She proposes that rather than looking at either of the two bodies (Frank and me, the screen and the shadow cast etc.) we turn our attention to a ‘third body’ in the space in-between the two. In her essay Coming to Writing, she writes in her signature evocative style ‘I am under the cosmic tent, under the canvas of my body and I gaze out … a Third Body (Troisième Corps) comes to us, a third sense of sight, and our other ears—between our two bodies our third body surges forth’.

When I stop looking directly at one performer or the other, in drag or no, and stop casting them in an identity, a very queer body emerges between us that affirms and troubles both of our existences. In Rootprints, Cixous goes so far as to suggest that music itself is this sex/gender difference: ‘because difference constitutes music, yes. Sound is a difference, is it not? … I think that one perceives sexual difference, once receives it and enjoys it in the same manner’. She’s not saying that this sound-difference is a strict male and female binary. Quite the opposite! The music she obsesses over destabilises gender. We interact with different people in different contexts and, for Cixous, the arrangement of bodies, our intimate relationships with these others, and even the resulting harmony of sound itself is always queer.

These ideas aren’t an abstract philosophy: we can feel them, see then, hear them in our common experiences of performing and listening. There’s the possibility to deconstruct normative perception in the name of liberation. This sensory third body as musical sex differences is brilliantly expressed in many of Julius Eastman’s ensemble works, particularly the delicately genderqueer Femenine (1974) and the unrelentingly homosexual Gay Guerilla (1980). Both are written in Eastman’s signature ‘basic’ style, an aesthetic that ultimately saw his ostracized from traditional concert and academic institutions. His compositions breached the acceptable, arguably fashionable uses of sound of the time to the extent that performing them disrupted the very essence of what we hear and see on the stage.

Femenine, scored for ten performers on a variety of instruments, questions the relationships between very different bodies. It’s underpinned by a mechanical jingling which persists throughout—it’s the first and last sound we hear. The jingling is our first hint at something deliberately and resolutely ‘other’. It’s always invisible, though always audible, and because of this it’s always other to us and maybe even other to itself. And yet it defines the structure of the piece and the instrumentalists’ performance. This sound is that which is not on stage but, because of its difference with the performers, redefines this space and the relationships between the performers. ‘There’s something prominent off the stage!’ ‘Where do we look?’ ‘Who do we listen to to hear the most persistent character in the piece?’ We look straight on at the stage in vain, and lose any certainty over the identity of the performers we might have had. In their place a new, indeterminate space that has never been inhabited by the heterosexual body or perception is legitimized.

The performers’ sound gradually evolves over the seventy minute long performance, always centred on E-flat and F. Because of this, there is a sense of nothing happening; the changes between each section are so subtle that they may as well be identical to the last. It’s a meditation on drag (specifically feminine men). In Butler’s theory of gender performativity gender isn’t constant over time, but repeated imitations of a gender that never had an origin. Each iteration attempts to replicate the one before and some origin, and every time there are changes in representing what came before. We have a very different conception of male and female and the relationship between the two in 2022 than we had only ten years ago. Although the sound in Femenine has completely changed by the end we hear it as an imitation of a sound at the beginning that was never there to begin with. In the same way that a third body emerges between the performers and the mechanised jingling these third bodies emerge between who the performers are and were.

Of course Eastman’s compositions deal not only with sexual but racial experiences, exposing the intersections between the two. Alexander Liebman, in ‘Nothing to Practice’: Julius Eastman, queer composition, and Black sonic geographies, unpacks the relationship between black and gay bodies in space in Gay Guerilla. Written for four pianos, it asks us to consider what in-betweens exist between like sounds. It is within blackness and male homosexuality, and what the possibilities for difference are between like bodies. Unlike Femenine, there is no offstage jingle, no distinction in timbre that immediately signals a disruption of space.

Perhaps it’s because each pianist plays similar material, because it’s homogeneous from beginning to end that a focus on one or the other pianist or even on the whole doesn’t reveal the full story. As an audience we are faced with something wholly other than us that has no pretence of inviting us into their world. The black gay stands on stage (as Eastman did during an infamous performance of John Cage’s Song Books in 1971) and, instead of saying ‘I am integrating myself into your space’ they say ‘this space is now mine; you may listen but this space is other to you’. Eastman had no desire to normalize black and gay identities. Liebman writes that Eastman maintained the idea of blackness and homosexuality as pathologies so that he might, through an embodied performance, actively reclaim these histories in white, normative spaces. The effect is the same as Femenine, if more politically ostentatious. To move through that which is already inaudible or to claim the audible space so that it becomes inaudible to the other both create third bodies in musical spaces.

These experiences also have a clear parallel with disabled lives. The struggles for queer, black, and disabled rights make the same demands: the right for our bodies to occupy public and private spaces, and to have access to social and medical services on our own terms. This was made all the more visible during the pandemic as immunocompromised people were in lockdown indefinitely. This wasn’t a loss of their viability. We saw these people, heard them, walked with them where their absence was felt outside. What was needed wasn’t to bring these people out onto the street but to make staying at home legitimate. And through this change in the in-between relationship of bodies was radically altered, not only were our public and private spaces queered, but the ways in which we could make music disrupted in the name of access.

And so I return to Rocky Horror, and in particular the character Dr Everett Scott. Dr Scott is the morally conservative counterpart to Frank’s literally alien, degenerate pedagogy. And although he’s in a wheelchair he has no difficult navigating the ‘Frankenstein-place’ mansion. Frank forcibly drags him to the lab using an electromagnet, calling attention to his disability, but there’s no sense that he is restricted in where he can go. However, it isn’t until the song “Don’t Dream It. Be It” that Dr Scott really engages with unconventional cast of characters. ‘Don’t dream it, be it’ is Frank’s final lesson, aimed at both the cast and the audience. Dr Scott is the last to join in, waiting in the wings with a blanket over his legs. He slowly pulls the blanket back to reveal high-heels and stockings —‘my life will be lived for the thrills…’—and it’s even possible that he had these on when he arrived! He rolls out of the wings, showing off his transvestite legs, bicycle kicking across the stage. What does he want to be? What do we want to be in the audience? He doesn’t dream of not being in a wheelchair, he has no desire to dive into the orgy with everyone else. He wants to cross the stage in his own way. He disrupts the geography of the stage, framing himself as an other, emphasising his impairment, in a mutual relationship with the able bodies that reveals new ways to exist.

In The Queer Pedagogy of Dr. Frank-N-Furter, Zachary Lamm notes that this destabilizing queerness ‘does no harm to the real world but brings pleasure to both on-screen participants and viewers’ (2008:197). There’s potential in these normative, ‘real world’ spaces. It’s within these worlds that we might find new, queer ways to make music. A queer body occupying a straight position is not enough. This disables those who cannot authentically exist in such spaces—Butch lesbians who cannot pass, black people who refuse to mask, impaired people who cannot go outside. Similarly, in In Search of the Authentic Queer Epiphany, Ben Hixon writes that disability narratives in Rocky Horror ‘may work toward allowing the queer to remain queer and free from inculcation by the pernicious tendrils of the happily normal ever after’. This is an important lesson for us as musicians—we’re often too concerned with who is in the centre of the stage that we forget to turn towards the unoccupied spaces in-between, to hear across oblique angles. We mustn’t be content with Jamie Barton waving a pride flag at the Last Night of the Proms in 2019, especially during the imperialist Rule Britannia. There’s a politically disruptive power in where we are inaudible and invisible. Dr Scott, Frank-N-Furter, Cixous, and Eastman encourage us not to look for an affirmation of identity, to see queer and disabled bodies in the centre of the stage, but where we’re spaced apart, where we’re tucked away in a corner, where we can compose, perform, and listen in ways that’ll re-orient, even queer our bodies.Page Break

References:

CIXOUS, H. ed. Jenson, D. intro. Suleiman, S. R. trans. Cornell, S., Jenson, D., Liddle, A., Sellers, S. (1991) “Coming to Writing” and Other Essays (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press).

CIXOUS, H. & CALLE-GRUBE, M. trans. Prenowitz, E. (1994/1997) Hélène Cixous Rootprints: Memory and Life Writing (London and New York: Routledge).

LAMM Z. (2008) ‘The Queer Pedagogy of Dr. Frank-N-Furter. Weinstock, J. A. (ed.) Reading Rocky Horror: The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Popular Culture (New York: Palgrave Macmillan) pp. 193-206.

LIEBMAN, A. (2021) ‘‘Nothing to Practice’: Julius Eastman, queer composition, and Black sonic geographies’. cultural geographies November 2021 (Sage) pp. 1-17.

j.n.m. redelinghuys is a South African born composer, performer, and musicologist based in York UK. Ze studied clarinet with Shannon Mowday and Morné van Heerden, piano with Maralie Stolp, organ with Kevin Kraak, and composition with Clare Loveday. Ze graduated from the University of Cambridge with a BA (Hons) specializing in composition, and an MRes from the University of York supervised by Prof. Roger Marsh. Ze is currently completing a PhD at York supervised by Prof. Bill Brooks examining the experience of embodiment in music-making through experimental composition, phenomenology, and queer theory.

https://jamesredelinghuys.com/