In celebration of LGBTQ+ History Month, we invited writers, researchers and thinkers to pitch us editorial on queer music, sounds and the people who make it. This article exploring the role of community in electronic music is by writer and photographer Mallory Bea.

Dean Blunt was spending a lot of time in LA last year. He’s elusive and difficult to pin down, so when one of our friends tweeted “I think I just served Dean Blunt at my cafe” and another friend swore that she saw the East London artist playing tennis in Chinatown, we all laughed the idea off. It couldn’t have been true. I was curious though, and I looked up “Dean Blunt LA?” online and found a Reddit thread filled with people in Southern California wondering if they should buy gig tickets for a show of his from a link that hadn’t been shared on any sort of official outlet. Somehow, someone had found a show flyer online with Blunt listed as the headliner—which was a big deal—he hadn’t performed live in six or seven years. I bought two tickets just in case and woke up to a text message from a friend producing the event wondering how I’d found out about it. Before the link could be shared, it had already sold out.

Blunt isn’t the only UK artist to manufacture a sense of mysticism around his identity, ultimately resulting in a cult following. Cornwall-born Aphex Twin famously disappeared in 2001, then reappeared, then disappeared—he weaves and out of public space to release music with no rollout and seemingly no plan to do it again, causing digital chaos every time he does drop. There’s also Burial, the South London composer known for his haunting, atmospheric soundscapes, and who, despite his influence on the UK music scene, rarely makes public appearances and has never shared his real name. Whether intentional or not, these composers have participated in their own sort of branding. By using ambiguity as a tool to distinguish themselves from the mainstream, they’ve each manufactured an identity of the enigmatic and rare talent, an isolated and miraculous incident.

In a 2013 interview with Wired, Burial shared that this was just the way of the underground. According to him, to remain anonymous is to participate in tradition. Though this is pretty true of the 90s UK rave scene, by the time he gave that interview, the acid house scene he’s referencing hadn’t existed for almost two decades.

The same year that interview came out, London’s A.G. Cook formed PC Music. In just one year, the London based label would amass hundreds of thousands of plays on tracks uploaded to their SoundCloud from artists doing something quite similar to Burial, Dean Blunt and Aphex Twin—creating interesting, ethereal discographies and dropping them without saying much else. But while Burial and Aphex Twin are elusive, logged off, and seemingly isolated incidents, PC Music’s roster was avant-garde, online and effortlessly collaborative. The nature of PC Music is, well, fluid and fun, and the music press was convinced it wasn’t just a new sound from a collective pushing out towards the edges of pop but instead, a joke. This too, is tradition in electronic music—take the mainstream rejection of disco, for example.

In fact, much like disco, PC Music cropped up a new wave of electronic production, garnering attention from largely queer listeners who were drawn to the cross-pollination happening between artists both on the label and among their peers. I can understand why—rather than creating singular mythologies shrouded in mystery, PC Music was fostering connections by way of consistency, and consequently building a self-sustaining community among artists, their friends, and tapped-in listeners who wanted to signal not only their knowledge and appreciation of experimental music, but their belonging, connection and participation. People were buying the records not because they were afraid they’d never have the chance to again—as is the case with artists who appear very rarely and randomly—but because they saw themselves reflected in them.

We often see straight (or at least, straight presenting) white men at the centre of a genre’s height in popularity. It’s not always an accurate representation: most, if not all, foundational dance music—disco, garage, house etc—were created by queer and trans people, particularly queer and trans Black people. While Burial is mostly right about the tradition of anonymity, I wonder if he realised he was referencing a very queer tradition of going underground not to facilitate legacy, but instead to ensure safety.

Queer music spaces have historically been curated with more intention and formalities than others to ensure material safety. Sarah Thornton writes in her book, Club Cultures, that between 1988 and 1992 with the rise of the AIDS crisis and an increasingly homophobic government, queer people in the UK were isolating themselves into their own worlds and communities. Section 28 was introduced in 1988, prohibiting the “promotion of homosexuality”, swiftly forcing queer nightlife underground. Even in scratching the surface of the history of LGBTQ+ nightlife in the UK, it becomes abundantly clear that as much as ambiguity regarding identity might facilitate safety, a pillar as equally important is establishing trust, resulting in a real sense of responsibility and with that, community.

Imagine me now with a whiteboard, drawing on one side of it “ambiguity to facilitate mystery, resulting in legacy” with Aphex Twin et al underneath and on the other “ambiguity to facilitate safety, resulting in community building” with Sophie and PC Music underneath. The common thread present through both of these little trees is more wholesome than you might think: the desire for belonging. There’s something world-building and special about participating in something that maybe not everyone knows about.

On one side of the coin, anonymity is what made those Dean Blunt sightings feel so surreal, and on the other side, it’s what has facilitated safety for queer and trans people for decades. The British tradition to keep things ambiguous in dance music impacts the way we consume it, the way we organise nightlife, and the way we engage one another. To take the risk in staying anonymous, we need to rely on one another for collaboration and support. I think it’s time we turn our attention and celebration towards the queer and trans world builders who time and time again invite the most on-the-fringes of us to belong to something.

About Mallory Bea

Mallory Bea is a writer and photographer based between Los Angeles, CA and London, England. Moved by songbirds, she's had personal research published by the Audubon Society. She's currently a research reader at the Octavia E. Butler archive at The Huntington and a monthly radio resident at Dublab. She loves earth and her neighbours.

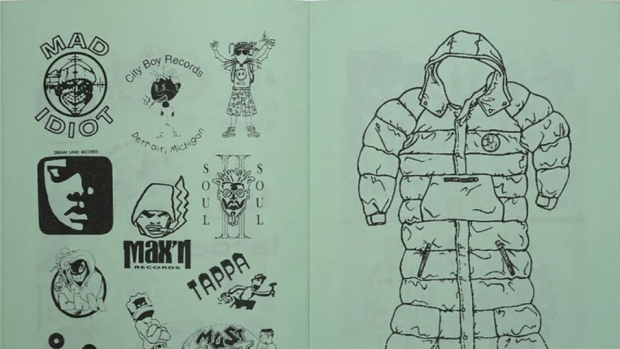

Cover image scanned from RUDEBOYS: Mascots of the Underground from Dub to Rave collected by Joe Resampled, 2023