Gwen Siôn, a grant winner of Climate. Sound. Change, talks us through the experience of creating 'HS2 Ghostlands', a multidisciplinary arts and research project created in response to the climate emergency and HS2.

Gwen Siôn is an experimental composer, pianist, producer and multidisciplinary artist

In early 2021, Gwen was selected as a grant winner as part of our Climate. Sound. Change. - an open call on the British Music Collection supporting composers to create new works that respond to the climate emergency. Here Gwen talks us through the making of her work HS2 Ghostlands, a multidisciplinary arts and research project created in response to the climate emergency and HS2.

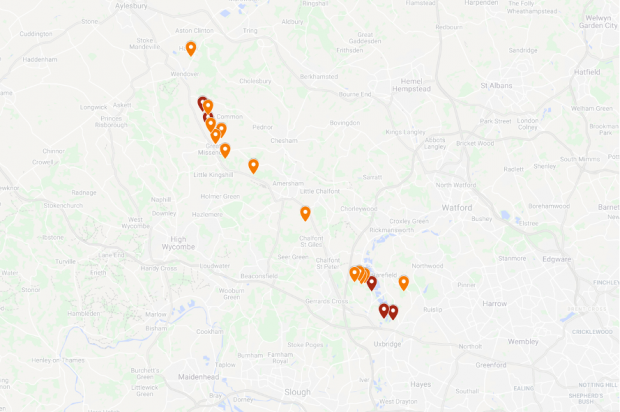

Between January and June 2021 I spent six months immersing myself in local woodlands under threat from HS2 (the high-speed rail network currently under construction in England). During this time I made a body of work called ‘HS2 Ghostlands’, a multi-disciplinary arts and research project created in response to the climate emergency and HS2. The project aims to highlight issues of deforestation, habitat destruction and biodiversity loss as a political act to record and preserve UK woodland. ‘HS2 Ghostlands’ is the result of working on location at 18 specific sites across Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire and the outskirts of London collecting field recordings and undertaking extensive research into HS2 and its environmental impact (the permanent destruction of 108 ancient UK woodlands and wildlife habitats). The final outcome of the project includes a digital archive of raw audio recordings in the form of an interactive sound map, a set of musical instruments hand-built by recycling natural materials found at the locations (such as fallen or felled tree branches) and a newly composed piece of experimental music.

The work aims to capture a particular moment in time by exploring the ghostly, liminal landscapes of these endangered woodlands through acts of mapping and translation, musical composition and archival processes such as field recording and photographic documentation. The purpose of 'HS2 Ghostlands' is not only to raise awareness of the environmental destruction caused by HS2 but also to preserve a record of the sites in an attempt to memorialise these soon to be lost woodland spaces and enable a transportive sonic encounter with them. I wanted to create a kind of fragmented resource explored through virtual sound artefacts, an immortalised digital space that could exist beyond the loss of the physical locations, one which could potentially facilitate a continuing point of contact between the public and these natural environments, making them accessible even after their destruction.

I am really interested in processes of translation and transformation. The experimental music piece, titled Ghostlands, which I created as part of this project was about experimenting with ways of interpreting the landscape in musical terms, trying to translate the experience of being present within these spaces and exploring how composition can be used as a means of mapping space and the cultural, ecological and socio-political significance of space. The piece combines all the environmental audio recordings of the 18 locations with original musical compositions. These compositions were created in response to the sites using found natural materials as instruments alongside vocal, multi-instrumental and electronic compositions inspired by reading the shapes, colours, textures and structures found in the visual landscape of the woodland as a musical score. Some melodic elements are also inspired by echoing patterns in birdsong heard at the locations and some phrases are directly translated from the birdsong itself by converting the audio data of recordings into MIDI data which was then assigned the voice of an acoustic piano. Ghostlands uses a mix of traditional acoustic instruments, electronic instruments, vocals, a variety of hardware devices and my own hand-built instruments. By creating instruments from fragments of the landscape, such as fallen or felled branches, the musical compositions are not only framed by the sounds of the woodland in the field recordings but are also made from the sites themselves, they literally resonate through the dead wood of the locations.

Spending time in these spaces had a profound effect on me. There was a strange tension between the tranquillity of nature and the precariousness of the situation, the ominous feeling of knowing that these spaces were about to be destroyed. This really did make the locations feel ghostly. An eerie surrealness was evoked by seeing public footpath and bridleway signs overlayed with “DO NOT ENTER” in bold, red print and ancient oak trees enclosed by tall fences and placards warning of patrolling guard dogs and security. Routes that would previously have been used to immerse ourselves in nature and celebrate it were now forbidden, shut off and used for a new purpose: to erase it. This tension created a strange dynamic, a stark division between natural and human worlds. Day by day these locations felt more temporary as their destruction loomed. The more time I spent in these woodlands, the more urgent it felt to capture a trace of them before they were lost.

The initial idea for my project was to work at one or two sites and to compose a piece of music inspired by the experience, but the more I witnessed the environmental impact of HS2 first-hand on woodlands near my home, the more I understood the scale of destruction and I began thinking of the project on a larger scale. I wanted to work in more locations and to find a way of acknowledging the presence and importance of these irreplaceable spaces. The project grew as I began researching all the affected sites within a 20-mile radius of my home. I decided that I wanted to work in all the locations within this vicinity and began recording at the 18 woodlands between London and Aylesbury suffering both the direct and secondary effects of HS2. I was working on location, collecting field recordings and amassing material, but I wanted to do more than just write a piece of music, I wanted to preserve something perceptible from these spaces, I wanted to present the unadulterated sounds of these woodlands in order to give their voices a platform in their own right without imposing my voice onto them. It was at this point that the project really evolved and I began creating an archive of the sounds I was collecting as a means of preserving a memory of these spaces. The project quickly became about trying to create an accurate auditory record of as many impacted locations in my local area as I could before it was too late and finding a way of presenting this archive in addition to the experimental music piece I was composing. I decided to create the interactive sound map as a way for people to explore this archive of sounds. I was interested in trying to create an immersive sonic experience that could provide a way of engaging with these spaces virtually, beyond their disappearance, and a map felt like the right kind of portal to navigate that and root you in a location.

As time went on, the more research I did and the more locations I worked in, the more aware I became of the corruption embedded in HS2 and the environmental crimes that were being committed. Many of these ancient woodlands were extremely important ecosystems, home to many diverse and thriving wildlife habitats yet they were being destroyed without proper licences. I began seeing the way HS2 was being managed, witnessing illegal felling practices with no ecologist on site at protected locations where felling was prohibited under environmental law, as they were home to extremely rare wildlife species. For example, evidence of barbastelle bats, a protected species and one the UK’s rarest bat species, were found in Jones Hill Wood where HS2 were illegally felling without having carried out proper wildlife surveys or having obtained the correct licenses. Loss of woodland is thought to be the primary reason that these bats are listed as “near threatened” on the global IUCN red list.

I spent many long, frosty, dim-lit mornings patiently waiting for the dawn chorus, still and silent, early enough to avoid the sound of chainsaws that would roar through the trees later in the day. I felt the character of the woodlands change over the three seasons I worked on the project. I lay flat on the earth each day, trying to blend into the forest floor, as ghostly and inconspicuous as possible. The field mic was placed on snow-covered ground when I started in winter, next to eager saplings in spring and surrounded by luscious greenery when the project ended in summer. The challenges of capturing an accurate environmental recording require you to become extremely delicate, almost camouflaged in your surroundings and demand prolonged periods of discipline, patience, stillness and silence in all weather conditions which force you into a meditative state of deep listening and acute sensory awareness. This became increasingly challenging with time as felling had begun in some of the sites. What was taking place at these woodlands meant that the process of working on location for this project was fraught with difficulties. By the end it got to the point where even just the act of being present in these spaces became highly politicised and very difficult due to the excessive HS2 security presence at some sites. This made recording extremely challenging and called for guerrilla tactics including lots of stealthy movements, fence jumping, ignoring road closure signs, hiding from security and, embarrassingly, impersonating a council officer at one point.

There were also many challenges presented as the project took place during the pandemic which meant it was essential for me to develop new ways of working and engage in a deeply reflective creative process. Coming to terms with the huge societal change which happened as a result of covid and not having access to materials, tools or a proper studio setting was extremely challenging at times. As I also had to shield throughout the pandemic, which had a huge knock-on effect on my work, I had to be completely self-sufficient and do things in a very solitary and DIY way. My working practice had to shift significantly, having to focus solely on using found materials and rural outdoor lone-working away from other people or working from home, using my flat as a make-shift studio and workshop space. I not only had to adapt my way of working but my way of thinking, I had to embrace these challenges and find ways of being extremely resourceful with limited materials. Using the landscape around me was integral to the project as it was my only point of contact with the outside world. The challenges presented by the pandemic and the reflective process they demanded ended up shaping the entire work, utilising the tools I had to hand and recycling found natural materials and environmental sounds. Covid also meant that I had to think about presentation in terms of creating a work that would be accessible in a digital space rather than a physical one.

Despite the pandemic making the working process behind this project a lonely experience at times and the technical and material challenges more difficult, the pandemic actually meant that I engaged with the natural environment around me in a much deeper and more mindful way, for which I am extremely grateful. The work itself and the intensity of the process behind it would not have been the same had it not been for the pandemic. The project became about responding to the current situation around me, demanding both a sense of immediacy and the patient stillness necessary to be mindfully engaged in the present environment. By actively engaging with the woodland, practising deep listening, recording, archiving, using and responding to environmental sounds and natural materials, I hoped that the work could find a voice to celebrate these woodlands and that it might present ways of engaging with these spaces beyond their physical existence.

To access ‘HS2 Ghostlands’ and explore the sonic archive and interactive sound map, the musical composition and photographic documentation of the instruments and locations visit: https://hs2ghostlands.co.uk/